To paraphrase Xiaoyu's mom, "Xiaoyu is already a sophomore! The implication is that he is as mature as an adult in his twenties or thirties even in the second grade of elementary school.

"Why is it that whenever he is asked about schoolwork or big questions in his life, he always grabs a pencil or an eraser and rubs it in his hand; if he can't grab something, he even plays with his clothesline, but he can't concentrate on what the adults are saying? What's worse, he even brought this bad habit to school. When the teacher asked him to memorize the text, he still played with his coat corner as he did at home, not caring about it. When he is in class, he touches everything and fiddles with everything, not paying attention at all."

At this point, Xiaoyu's mom seems to have awakened some of her memories: "Although I said he was inattentive, he was able to answer questions about everything. It was as if his brain was growing on his fingers, and he had to rub and move his fingers to get it to work.

"Oops! Why can't he listen and answer questions like the other kids? Xiaoyu is already a sophomore!" Mom couldn't stop using the usual phrases to draw conclusions.

The world at your fingertips

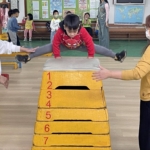

Before babies are able to master language and express their joys, sorrows, and fantasies, they will slowly extend their tentacles with their fingers in the survival environment. They will play with their fingers and toes, grab the glasses on their father's face, and sneak up on their mother's slicked back hair to distinguish between you, me, and him. As the child grows up and begins to follow the command of the brain, he or she is able to knock and play with pots and pans and objects of different shapes. While touching, the child also builds up the brain's ability to differentiate, summarize, and integrate abstract concepts in the future.

From infancy to the end of our lives, our sense of touch, in different forms, has a continuous and far-reaching impact on our learning. Experimental studies have found that tactile sense, like visual sense, plays an important role in learning and memory, and that just a small activity such as manipulating blocks can affect our future mathematical and thinking skills.

Wolfken, a professor of education at Florida State University in the United States, published his findings in 2006 after tracking and studying 37 children in daycare centers for 16 years. When the study began, the children were only four years old. The research team observed and recorded the children's manipulation of building blocks. The research team then followed time and collected the children's test results in grades 3, 5, and 7, as well as their math and science electives and classes at school, and their academic performance in high school. The results showed that children who were actively engaged and mature in the use of blocks at age four did significantly better than their peers in math and science in seventh grade and high school.

Move your hands, move your mind.

In 2006, North Carolina State University science education professor Jones's research team wanted to find out whether tactile sensation could help students memorize more content and increase learning efficiency, so they invited 36 students from national and high school elective science courses to participate in an experiment to observe bacteria. One group of students was able to feel the tactile sensations of measuring, pushing, cutting, and touching through a remote control connected to a microscope. The other group of students could only get visual feedback through the remote control, but lacked the tactile sensation of being in the real world.

At the end of the experiment, the research team asked two groups of students to fill out a test questionnaire, and found that the students with tactile feedback had significantly better test results and found the program lively and interesting.

Throughout the course of human life, we must constantly learn to recognize places, words, concepts, and people and things with varying degrees of nuance. From birth, humans learn about concrete objects by touching them; as they mature, they are able to translate these experiences into abstract concepts.

With his fifteen years of research in the field of tactile learning, Capella, an educator engaged in teaching training and research on programs and tools, has found that hands-on tactile learning is the driving force behind the construction of four thinking skills that are indispensable to people's learning. These are: recognizing similarities and differences, discovering patterns in how things work, integrating information, and being able to think from multiple perspectives.

Tactile stimulation not only makes children's learning in life and in the classroom more efficient, but it also makes their brains think better. Therefore, neuroscientists would like to tell Xiaoyu's mom that when Xiaoyu faces challenges in school and life, he will intuitively seek tactile stimulation to help him concentrate more on his thinking and face the challenges. For children who are tactile learners, their brains grow on their fingertips, and when their hands move, their brains will move with them.

Brain neuroscientists have also reminded educators to design more hands-on and experiential exercises in the classroom, not only to remember and learn quickly, but also to arouse the enthusiasm of children to pursue the root cause.

Wang Xiuyuan (Neurological Trainer)◎Works